credit: super8legacies

60s Counterculture

It’s still inconceivable to me just how blasphemous it was for a couple of unwed college kids to shack up in 1965, in Williamsburg, Virginia. But my grandfather’s response (to my parents living together) was a stark reminder of just how big the gap was between generations—or at least between my grandparents and the hippie culture my mom and dad were becoming a part of. In fact, the term “generation gap” was coined in the 60s to describe that very phenomenon of distance between the beliefs and cultural norms ascribed to by young people vs. their parents. Incidentally, my mother’s parents were equally conservative though not in the Southern way, and were none too pleased either with the freewheeling lifestyle on the horizon.

People of their generation and upbringing were still very much about appearances, reputation and propriety. My parents, on the other hand, didn’t live under that same guise at all. Living together was a total non-issue; they had no self-consciousness about it. The notion of “living in sin”—whether sin of the deeply religious kind or sin of the “dont-let-people-see-us-look-bad” kind—meant nothing to them. Sin itself didn’t even register.

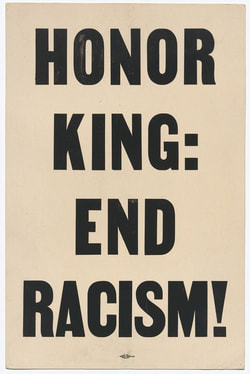

Contemplating that gaping divide, I always had it as mere coincidence that my grandparents on both sides were particularly conservative and against the union of my parents. It has taken a lot of study and imagination for me to acknowledge just how radically different things were for parents of that era whose children were of the counterculture. The psychological limitations of my grandparents—that inability for them to grasp or relate to what was happening with Hippies and the Civil Rights movement and anti-Vietnam War activism—accentuated by a desperate need to hold on to the last vestiges of 1950s wholesomeness, must’ve been excruciating. In less than two decades, my grandparents would have heard the swoony melodies of their day turn into loud rock-n-roll and protest songs. Suddenly music took on all kinds of meaning that would expose any shallow, smarmy-ness of previous generations, and all those nice-looking kids with crew-cuts would soon become long-haired, bearded hippies who smoked weed. Their sons and daughters were beyond their command and their old world was rapidly aging.

I’m sure it was all a bit much.

He’s reading Rod McKuen, author of Stanyan Street & Other Sorrows, and sends along a quote from Richard Fariña, singer/songwriter and author of Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me, the cult classic that spoke to a generation of hippie college students who shirked that which came before. (Incidentally, Richard Fariña was killed in a motorcycle accident down in Carmel, California, just two days after his book came out.)

I recognize the name Richard Fariña and wife Mimi (whose sister is Joan Baez). My mother has talked about their music over the years and I had previously stumbled upon this one haunting song they sing with dulcimer called “Bold Marauder.”

Curious to see what was speaking to my father in December of 1967 in San Francisco, I look it up online. The back cover of the Four Square / New English Library 1968 edition reads: |

Our young cat Eddie with the rucksack would continue to wander, make scenes and wreck the “campus” well into his own 60s—never quite getting his head together nor conquering the world—yet still holding some sort of vision that he could, and would.

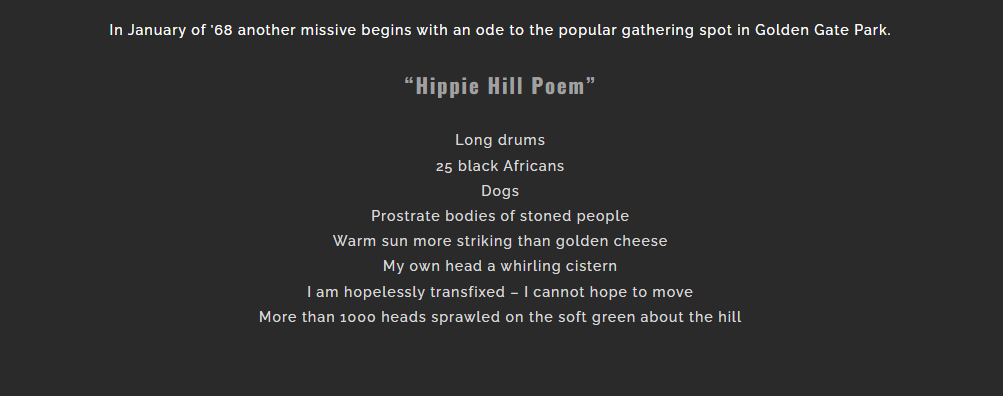

Admittedly too stoned to write more, Daddy mentions riots on campuses all over California, muses whether dolphins are more intelligent than humans, and leaves my mother with a poem about stallions.

“Paralized as such, I will endeavor to write you, saying only what must be said.”

It turns out my grandmother would be coming out within a week and staying at his apartment for four to six weeks. Thus, he’s asking my mom to postpone her visit until March.

As I read this aloud sitting across from my mother 51 years later, I’m like, “How on earth is he going to get it together in seven days?” Just knowing my father’s habits in later years I can’t imagine this coming to fruition in the earlier ones. “And how on earth is he going to keep it together for six weeks?”

“Just wait till you read the next page,” says my mother, “you have no idea.”

My mother had already had her taste of his parents’ disapproval of the relationship back in Williamsburg, and they had already gone to great lengths to get her own parents involved several times around whatever impropriety was seriously yanking their chain. So my mother wasn’t exactly advertising the fact she was going out to San Francisco and my father sure wasn’t letting anyone know.

17 days later another letter arrives. It reads:

“Better shed any evidence you happen to have around of grass. Grizzly scene here. My mother went snooping into every nook and cranny of the apartment; read nine letters, all from Dick and you, as well as discovering the jar of seeds and stems (which I destroyed immediately). You know, and no doubt, have felt the repercussions of her discovery. She called the Oakland Examination…my file is being mailed to my father. Jesus on a crutch! I suspect apartment will be placed under surveillance and I will be recalled by the SS [Selective Service] for another examination. I am feeling mildly suicidal. If I can beat this rag, I am going to vanish – from everyone. No one, especially my parents, will ever know of my whereabouts, and I’ll have another name. I pray to God (whatever he is) that you have not been nabbed for possession; destroy this instantly after reading! Letters are more lethal than napalm.

Baby – you cannot return to S.F. If our current relationship continues it will destroy us both – or me anyhow; my parents would readily clamp either of us behind bars to stop it. My mother implies that she has had my father notify your parents. I’m sorry.

You know how I laughed off the physical [SS] as if I had put something over on them. In truth, I didn’t. I have been ridden with guilt, drugs, booze, hang-ups and us for so long that I really AM as I told the shrink.”

My father had seriously fucked himself up with drugs and alcohol the day he went for the draft exam. This was one of the few ways to effectively resist the draft in 1967. Otherwise, your main options would have been being an undergraduate student still in school, being on the police force or studying or serving in the medical field or being a married man with dependent children. Clearly my father was going for: Classification IV – F Registrant not qualified for military service. And he must’ve panicked at the idea of those Selective Service notes about his mental and physical state getting into the hands of his father. He could see the whole crazy-ass world of it crashing down. As he indicates in his letter, it was as though he really was as fucked up in real life as he’d made himself out to be for the draft board in Oakland.

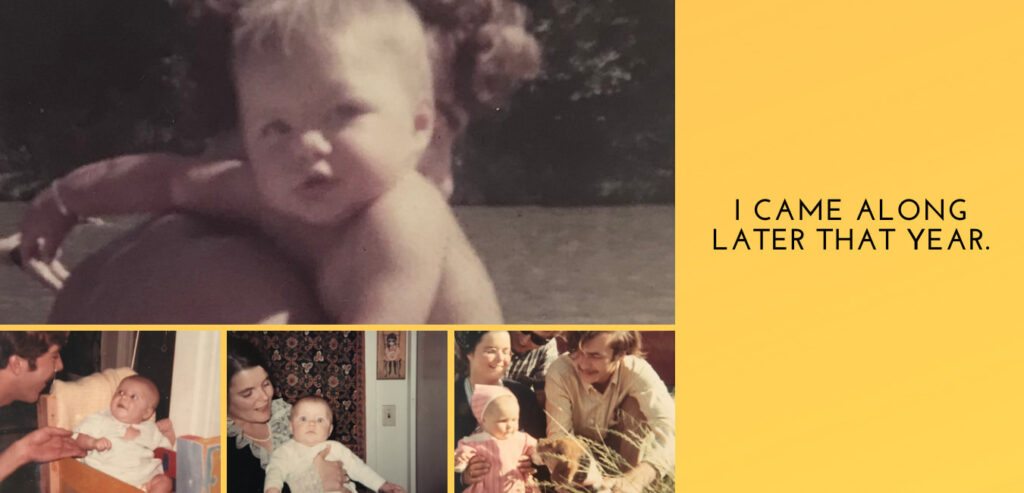

Incidentally, when I was about a year old, Richard Nixon signed an amendment to the Military Selective Service Act of 1967, which began the first ever draft lottery from which young men’s names were randomly picked by birth date and year. As much as I interrupted the flow of my father’s life, perhaps I also helped save it. Thirty years later I would voluntarily enter Vietnam, traveling overland from the border of Cambodia and catching a taxi into Saigon with an American guy who had sprinted for the same ride. We ended up traveling around the Mekong Delta and throughout South Vietnam for 10 days, being gawked and smiled at, treated kindly by the South Vietnamese, and spending one particularly unforgettable evening dancing in the streets of Chau Doc to Santana tunes with a toothless Vietnamese grandmother and a big-bellied, shirtless happy Buddha dude. In Saigon, at the museum, I learned that in Vietnam they call it “the American war.”

Stop the Draft Week, October 20, 1967, Oakland, California

Oakland Public Library, Oakland History Room and Maps Division

It’s hard for me to imagine how real the stress and panic of all of this would have been for my father. Not just the draft-dodging but the parents, the pot, the perceived danger to his way of life. After all, marijuana is now medically legal in 33 states and recreationally legal in 12 as well as Washington, D.C. In 2020 most people surveyed seem to be in favor of recreational use in general.

But in 1968?

Back then the Boggs Act of 1952 and the Narcotics Control Act of 1956 were still in place, making first-time possession of pot punishable by ten years in prison and up to $20,000 in fines. Not to mention the atmosphere was hyper-charged with protests, riots and dissent.

Across the bridge in Oakland, the newly formed Black Panther Party for Self Defense had amassed 2,000 members who were standing for their right to protect themselves against the police. That very February at South Carolina State, 33 activists were shot by local cops and three of them were killed. The ever-paranoid and shit-swirling J. Edgar Hoover was still at the helm of the FBI, going after anyone or group he deemed the least bit subversive and using covert and often illegal tactics like wiretapping to try to expose everyone from Martin Luther King to Bobby Kennedy.

January 1968 had also seen the Tet Offensive when the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong launched a series of devastating military attacks on South Vietnam. Although it ultimately helped turn the tide of American opinion about the war, at the time the mood was one of shock and horror. In my father’s mind, and quite realistically, if he had been plucked out as a draft-dodger, it could have meant being picked up by the U.S. Marshals or the FBI, being interrogated and investigated, and ultimately left with the abysmal option of jail time or going to Vietnam after all.

Add to all that, my grandparents–in their own “reefer madness“–might themselves have had my father put in jail. That’s how insane it all was.

Nonetheless, Daddy wrote in Bobby Kennedy’s name on the ballot in November of ’68, against Nixon.

” This is the finest English-speaking city on earth! They named it after you and I and the saint. If you ever come back I’ll be here or dead or striding the tracks beyond San Miguel de Allende tequila fist-on-neck, Camel in me yap, coonskin cap, counting 68, 947 and still pumping. (Cassady was a victim of methamphetamines.) I’ll never be a victim of anything except loss of will and spirit.” – letter posted from Daddy March 25, 1999 from San Francisco

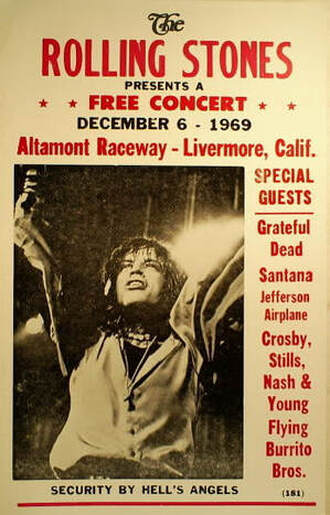

Altamont (West Coast Woodstock), December 6, 1969

When I was growing up, my mother would retell the story of the woman who wanted to hold me at Altamont and next thing they knew she had wandered off with me. I have this image in mind of my father sprinting after the woman, dodging all the drunk and stoned hippies sprawled on blankets.

We were way far back from the stage like most everyone else, unaware until the next day of Meredith Hunter, the Black teenager who had been stabbed to death by two Hell’s Angels hired as security for the event. Up by the stage, the Angels had been hostile and brutal. Not the kind of peace and love people were used to. Even Mick Jagger couldn’t get things under control, as you can see in the Rolling Stones documentary Gimme Shelter, which chronicled the whole debacle. The footage also shows people completely tripped out of their minds in a display of debauchery that even makes me a little uptight.

Ultimately, there would be four deaths at Altamont (not all related to the Angels) and a clear signal that something had shifted.

Rob Kirkpatrick, author of 1969: The Year Everything Changed, writes, “Left on its own at the end of the decade and seemingly gathered at world’s end, the Altamont congregation straddled the line between freedom and anarchy and experienced the ugly underside of a generation’s collective dream.